a brief overview of

navajo nation land tenure

October 15, 2019

Historical Diné Land Management

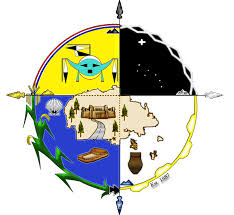

Historically, land in Diné Bikeyah was not held, but stewarded in clans led by a matriarch who was chosen unanimously. Acting as a land and clan manager, the matriarch was central to the smooth running of beneficial relationships with the land and among members of the clan. Settlements did not descend but were stewarded intact in the name of the clan (not unlike perpetual corporations).

Hwéeldi - Imprisonment at Fort Sumner (1864)

The historical Diné method of land management was at its most evolved just prior to Hwéeldi, the Long Walk, during which Diné cultivated lands were destroyed and Diné people rounded up and marched hundreds of miles into unsheltered, oppressive, and demeaning captivity at Fort Sumner over the course of 5 years. While in captivity, the people were organized into camps without regard to families and clans, intermingled with other captive tribes. There were many losses of life. The captives were allowed to return to a much diminished Diné Bikeyah, now called a reservation. While some families were able to resume cultivation in the old ways, many families had lost their matriarchs. Land once cultivated remained vacant season after season. To this day, vacant land on the Navajo Nation is considered as the customary land of a clan that will return.

In the decades following Hwéeldi, the reservation began to be managed through leases and permits issued in the names of individual adults, first by the BIA and then by the Tribe. Today, each adult is entitled to no more than one homesite lease and one farming or grazing permit. Under the lease and permit regime, land parcels are limited to single uses and may not be combined with other uses. Trust lands, distinct from allotments, are not required by federal law to be probated. Nevertheless, probate for leases and permits have come to be required under tribal law, resulting in smaller and smaller, use-limited parcels.

The scheme of leases and permits has had enormous negative impact on Diné families, displacing how families have organized themselves, and land use, for generations. The result is internal conflict of practically every Diné family regarding land, and a hasty and thoughtless reorganization of rural extended families into unfamiliar silos.

In the decades following Hwéeldi, the reservation began to be managed through leases and permits issued in the names of individual adults, first by the BIA and then by the Tribe. Today, each adult is entitled to no more than one homesite lease and one farming or grazing permit. Under the lease and permit regime, land parcels are limited to single uses and may not be combined with other uses. Trust lands, distinct from allotments, are not required by federal law to be probated. Nevertheless, probate for leases and permits have come to be required under tribal law, resulting in smaller and smaller, use-limited parcels.

The scheme of leases and permits has had enormous negative impact on Diné families, displacing how families have organized themselves, and land use, for generations. The result is internal conflict of practically every Diné family regarding land, and a hasty and thoughtless reorganization of rural extended families into unfamiliar silos.

Leases & Permits

The public continues to believe that most lease restrictions are imposed on them by federal requirements. However, this is not so. Beginning in 2006, the BIA began handing over leasing on the reservation to tribal control to be managed pursuant to lease regulations promulgated, entirely by choice, under tribal law. Congress gave the Tribe the privilege of self-management pursuant to the Navajo Leasing Act of 2000, provided that the Tribe substantially adopt the federal lease and permit scheme as tribal law. Business leasing came under Navajo Nation sole control when the Tribe passed business site leasing regulations in 2006. When the tribal General Leasing Act was passed in 2014, other surface leases came under tribal control, under tribal leasing law. (Since then, other tribes have been given greater flexibility than the Navajo Nation in their tribal leasing regulations under the HEARTH Act of 2012).

Red tape became far more complex under sole Navajo Nation management for many reasons, chiefly funding. Federal funds did not come with self-management. To cut costs, the Tribe began delegating pieces of the leasing process across its many divisions and programs, creating a bulky system with as many as 163 steps in the application process, and a lot of cost burdens placed on the people.

Reform Possibilities: 25 USC 415 provides statutory authority for surface leases on restricted Indian land, with regulations set forth at 25 CFR Part 162 for most leases and permits. However, federal law does not require that leases and permits be used. 25 CFR 162.006(b)(1)(vii) provides for an inherent tribal powers alternative (further discussed below).

Red tape became far more complex under sole Navajo Nation management for many reasons, chiefly funding. Federal funds did not come with self-management. To cut costs, the Tribe began delegating pieces of the leasing process across its many divisions and programs, creating a bulky system with as many as 163 steps in the application process, and a lot of cost burdens placed on the people.

Reform Possibilities: 25 USC 415 provides statutory authority for surface leases on restricted Indian land, with regulations set forth at 25 CFR Part 162 for most leases and permits. However, federal law does not require that leases and permits be used. 25 CFR 162.006(b)(1)(vii) provides for an inherent tribal powers alternative (further discussed below).

The Alternative of "Tribal Land Assignments" (Inherent Sovereign Powers)

25 CFR 162.006(b)(1)(vii) provides for a "tribal land assignment" (TLA) exception to leases, which a Tribe may provide for solely under tribal law, under inherent tribal powers. The BIA will not disturb these TLAs so long as the land may not be sold or encumbered beyond 5 years. Such TLAs can be configured along customary uses as they arise under inherent powers.

Tribal land assignments have never been statutorily developed on the Navajo Nation. However, tribal customary land use concepts have been pursued by the Navajo Nation courts.

Over many decades and many court opinions, the Navajo Nation courts have articulated Diné concepts such as Navajo land tenure, the "true" Diné nature of individual permits, customary land use areas, customary trusts, the Navajo oral will, Navajo probate, Navajo homestead, Navajo "immediate family" for distribution, the most logical heir, and other concepts important to the continuation of community land use practices. However, the English language terms have created some confusion. Additionally, the Tribe has lacked the expertise and capacity to develop these concepts in statutes and regulations.

Today, the federal govt. more and more encourages self-determination. Through the federal policy encouraging tribes to envision its own "integrated resource management planning" (IRMP) unique to its practices for future generations, tribes are strongly recommended to reverse the single-use land policy and pursue combined land uses, whatever the Tribe can envision. See these BIA IRMP resources: Guidelines for IRMP in Indian Country and A Tribal Executive's Guide to IRMP. Tribes are encouraged to establish an IRMP identifying "holistic management objectives that include quality of life, production goals and landscape descriptions of all designated resources that may include (but not be limited to) water, fish, wildlife, forestry, agriculture, minerals, and recreation, as well as community and municipal resources." There are, otherwise, no stringent conservation regulations over farming. However, the lease system is very deeply embedded on the Navajo Nation and most tribes.

Special Note: The Navajo Nation has begun contracting with outside planners to create IRMPs but the planners are unfamiliar with customary practices.

Tribal land assignments have never been statutorily developed on the Navajo Nation. However, tribal customary land use concepts have been pursued by the Navajo Nation courts.

Over many decades and many court opinions, the Navajo Nation courts have articulated Diné concepts such as Navajo land tenure, the "true" Diné nature of individual permits, customary land use areas, customary trusts, the Navajo oral will, Navajo probate, Navajo homestead, Navajo "immediate family" for distribution, the most logical heir, and other concepts important to the continuation of community land use practices. However, the English language terms have created some confusion. Additionally, the Tribe has lacked the expertise and capacity to develop these concepts in statutes and regulations.

Today, the federal govt. more and more encourages self-determination. Through the federal policy encouraging tribes to envision its own "integrated resource management planning" (IRMP) unique to its practices for future generations, tribes are strongly recommended to reverse the single-use land policy and pursue combined land uses, whatever the Tribe can envision. See these BIA IRMP resources: Guidelines for IRMP in Indian Country and A Tribal Executive's Guide to IRMP. Tribes are encouraged to establish an IRMP identifying "holistic management objectives that include quality of life, production goals and landscape descriptions of all designated resources that may include (but not be limited to) water, fish, wildlife, forestry, agriculture, minerals, and recreation, as well as community and municipal resources." There are, otherwise, no stringent conservation regulations over farming. However, the lease system is very deeply embedded on the Navajo Nation and most tribes.

Special Note: The Navajo Nation has begun contracting with outside planners to create IRMPs but the planners are unfamiliar with customary practices.

Limitations of Permits

Federal regulations at 25 CFR 162.007 have long allowed Tribes to issue permits in lieu of leases without need for BIA approval. However, the Tribe must regulate each permittee. It must make sure the permittee has a non-possessory right of access which may be terminated by the tribe at any time, that the permittee complies with environmental and cultural resource laws, and provides copies of permits to the BIA. The permits must be in individual names and are subject to federal concepts of leases and permits. The requirements flow from delegated trust responsibility.

The Tribe has relied on permits as the most autonomous method of managing even subsistence agriculture. Meanwhile, the tribal courts have declined to accept the great possessory limitations that permits impose. Each and every permittee is also individually subject to environmental and cultural compliance requirements one permittee at a time, which is why farmers and ranchers must each struggle to create conservation plans. Yet, large-scale regional conservation and environmental planning which would relieve individual permittee burdens is allowed by other laws, such as the American Indian Agricultural Resource Management Act of 2011 (AIARMA).

It must be emphasized that subsistence and small-scale tribal farming was never intended to be included in the lease or permit scheme. Note that 25 USC 415 provides for the leasing and permits of restricted Indian lands "for those farming purposes which require the making of a substantial investment in the improvement of the land for the production of specialized crops as determined by (the BIA) for a term of not to exceed twenty-five years." Subsistence farming is not included in this definition.

Reform Possibilities: The Tribe may articulate its community vision for future generations in an IRMP, that may include clan-based land stewardships or anything the community can envision for itself. The Tribe may also implement its community vision through tribal land assignments that are not constrained by federal concepts.

The Tribe has relied on permits as the most autonomous method of managing even subsistence agriculture. Meanwhile, the tribal courts have declined to accept the great possessory limitations that permits impose. Each and every permittee is also individually subject to environmental and cultural compliance requirements one permittee at a time, which is why farmers and ranchers must each struggle to create conservation plans. Yet, large-scale regional conservation and environmental planning which would relieve individual permittee burdens is allowed by other laws, such as the American Indian Agricultural Resource Management Act of 2011 (AIARMA).

It must be emphasized that subsistence and small-scale tribal farming was never intended to be included in the lease or permit scheme. Note that 25 USC 415 provides for the leasing and permits of restricted Indian lands "for those farming purposes which require the making of a substantial investment in the improvement of the land for the production of specialized crops as determined by (the BIA) for a term of not to exceed twenty-five years." Subsistence farming is not included in this definition.

Reform Possibilities: The Tribe may articulate its community vision for future generations in an IRMP, that may include clan-based land stewardships or anything the community can envision for itself. The Tribe may also implement its community vision through tribal land assignments that are not constrained by federal concepts.

Opening Up Possibilities for Farming

The AIARMA at 25 USC 3711(a)(2) specifically includes subsistence farming as an agricultural product that should be beneficially managed consistent with tribal self-determination. Tribes are encouraged to establish an IRMP identifying "holistic management objectives that include quality of life, production goals and landscape descriptions of all designated resources that may include (but not be limited to) water, fish, wildlife, forestry, agriculture, minerals, and recreation, as well as community and municipal resources." There are, otherwise, no stringent conservation regulations over farming.

Reform Need: Farming is the heart and soul of Diné community life in many parts of the reservation, yet because of the permit system, it is also the modern day cause of familial conflict. The Tribe needs help making an IRMP vision that will reduce or eliminate familial conflict in the area of farms, then making that vision real. A vision often spoken locally is a return to matriarch-managed lands that are not broken up into smaller and smaller pieces. In this time of federal IRMP and AIARMA policy, emphasizing tribal self-determination and a tribe's own vision for its future, such a return is possible, as well as any other vision the Tribe might have for its future generations.

Reform Need: Farming is the heart and soul of Diné community life in many parts of the reservation, yet because of the permit system, it is also the modern day cause of familial conflict. The Tribe needs help making an IRMP vision that will reduce or eliminate familial conflict in the area of farms, then making that vision real. A vision often spoken locally is a return to matriarch-managed lands that are not broken up into smaller and smaller pieces. In this time of federal IRMP and AIARMA policy, emphasizing tribal self-determination and a tribe's own vision for its future, such a return is possible, as well as any other vision the Tribe might have for its future generations.

Regulation of Livestock

Navajo Nation livestock grazing are subject to regulations specifically covering Navajo Nation livestock, at 25 CFR 167. It is an absolute requirement.

Reform Possibilities: The AIARMA covering "Indian agricultural lands" (farm and rangelands) specifically provides for regulatory waivers upon a tribe establishing an IRMP. However, the bar on grazing-related land conservation is high.

Reform Possibilities: The AIARMA covering "Indian agricultural lands" (farm and rangelands) specifically provides for regulatory waivers upon a tribe establishing an IRMP. However, the bar on grazing-related land conservation is high.

© Josey Foo, J.D., M.F.A.

Navajo Family Voices

Indian Country Grassroots Support

Navajo Family Voices

Indian Country Grassroots Support

Program Resource Links:

environmental & Cultural protections

impacting community land use

The below section is still being written, thank you for your patience. Ahee' hee.

NNEPA

The Navajo Nation implements its own environmental policy enacted under tribal law that has been duly approved by the BIA. However, far from easing burdens, the Navajo Nation Environmental Policy Act (NNEPA) adds wider protective language than the federal National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) policy and also adds enforcement functions. While the NEPA would have applied only to actions under the federal trust responsibility or actions taken under federal grants, the NNEPA applies to "all persons and entities" and requires tribal agencies to prepare documentation on environmental impacts. At this time, lease and permit applicants large and small are required to provide business and conservation plans for NNEPA environmental review.

Navajo Nation Cultural Resource Protection Act (NNCRPA)

Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA)

National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA)

American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA)

Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)

Federal Land Management Policy Act

The Federal Land Management Policy Act of 1976 (per the Indian Affairs Manual Part 57, Chapter 7 and Wolberg and Reinhard 1997) (per the Indian Affairs Manual Part 57, Chapter 7 and Wolberg and Reinhard 1997)